In this post, we continue the conversation between Charlie and climatologist Gov Pavlicek. Gov responded to Charlie’s earlier comment. That discussion is here.

In this post, we continue the conversation between Charlie and climatologist Gov Pavlicek. Gov responded to Charlie’s earlier comment. That discussion is here.

GOV: “ECOLOGY” AND XENOPHOBIA

From Gov:

“Charlie, thanks for the thorough reply. I was astonished by the ecologists I know. I’d say they are not secretly conservative on this issue, they don’t seem to know it or acknowledge it. In all other aspects, like me, they are usually progressive when it comes to people or culture.

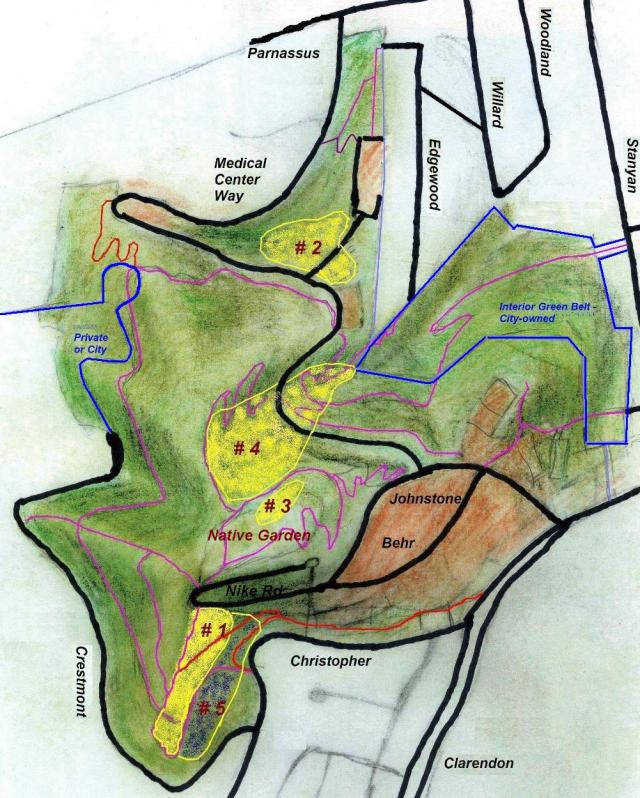

“On the other hand, I have read some comparisons between the homogenization of nature and culture in a sense that the latter is also “bad”: [that for instance] McDonalds in Nepal would be awful. [However], as with nature, the local people [actually] seem to enjoy it. In theNetherlands [NL] theUniversityofWageningen did research on which woodland forests visitors liked the most in NL. Out of 150 different pictures two clearly emerged as top favorites: one had beech in it, the other oak, and both had a Douglas fir clearly visible. They concluded that people do not reject and indeed like these trees.

“Separately, they asked the same respondents what they thought of exotic trees like Sitka spruce and Douglas fir. Again, respondents highly valued these trees. They rejected the idea of eradicating them because they somehow did not belong here — even after an explanation of why they were being removed in some woodlands. People felt these trees had every right to be there.

“In short: 65% of the respondents favored these trees, 20% were neutral and 15% in favor. Not unlike McDonalds in Nepal, or Mount Sutro forest in San Francisco. Should we get rid of things because 15% of a population wants it?

“I am not alone in finding the resemblance between ecological and cultural xenophobia striking. Researchers like Dov Sax, James Brown, Steve Gaines and Mark King note the same thing. Kate Rawles, a British philosopher, notes the same xenophobic and illogical thinking within [some] British conservation groups.

“It is also quite obvious that people can (and sometimes do) say the same thing about immigrants; and in both cases they base their arguments on exceptions and use examples to support their views. It just shows that (extreme) conservatism is not simply a right-wing thing. I have found the [charge of xenophobia] rejected with anger by ecologists. But a comparison leads to that conclusion.

“First: what is conservatism? It comes from conservare which means “to preserve”. In general we can say that most ecologist see it as a good thing to preserve global biodiversity, to preserve as many species as possible and reject the thought of extinctions and it is clear they want to preserve all kinds of habitats. Moreover, habitats that have changed over the last centuries are “restored” to how they supposedly looked. In what sense is this not conservative? How is that different from people who long for the good old days?

[In the previous exchange, Charlie said, “You mention global warming and think that ecologists, unlike climate scientists, have some racism-based bias and are secretly conservatives…”]

“Racist… I didn’t use that word. Xenophobic. Never used that, either, but indeed I do find it xenophobic or at least [tending] to it. Simply because there are a lot of organizations, lead by ecologists who strongly are:

- against globalisation of nature

- against introduction of species by man (other introductions seem to be fine)

- where possible, the are strongly in favor of eradication of plants and species they feel [unsuitable]

- They feel that new trees are not members of a certain ecosystem and fail to acknowledge the fact that these species form a new kind of ecosystem.

“That is the “xeno” part of it: Something that enters [an ecosystemafter] some randomly chosen point in time will always be a stranger. Everything before that time is no problem. Sometimes they tolerate the stranger, but they rarely accept him.

“The phobia (fear) comes from the many assumptions, demonizations and exaggerations we find in scientific and other literature by those ecologists. It is also clear in the value-laden wording that tell us they see [these species] as not belonging somewhere and causing harm simply by being there. ‘Alien’, ‘pests,’ ‘plagues,’ ‘prolific,’ to name a few.

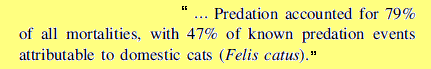

“It’s also apparent in the assumption that a new plant crowds out other plants and will lead to extinctions — even though research has shown this has never happened on a continent (Sax and Gaines, 2008, PNAS). This supports earlier research. At the University of Wageningen, research showed that 1 of 1,000 immigrant species become invasive — 999 do not. And how the newcomer enters the new habitat does not matter; whether it spreads by itself or is introduced by man has no influence on the outcome.

“In the comparison between climatologists and ecologists: No peer-reviewed research over the last ten or fifteen years challenges the theory that a rise in CO2 causes a rise in global temperatures. The same is true for the cigarette comparison. In ecology, this is not the case. Like global warming denialists, it [is] ecologists who revert to examples, assumptions and who actively seek media attention to tell us how evil immigrant species are. They are vocal like climate change denialists while not giving us any proof for an ‘invasional meltdown.’

“Climatologists in general are not nearly as vocal, even though their science is unchallenged. They also are quite clear where the uncertainties are and what their total influence is on global warming (for instance: cloudcover).

“Conservation biology is not a science if it tells others what’s right or wrong: It is an ideology. It’s possible to research all sorts of developments without attributing any value to a particular change. This also prevents others [from becoming] biased before they do their own research, or becoming indoctrinated with specific views on these changes. I think scientists should do everything not to be biased. Biases increase the chances of research being colored by personal preferences rather than scientific facts.

“A final point is that ecology deals with life. Particularly on the massive scale proposed by some ecologists, if we talk about life and death, we talk about ethics. And ethics should not defined by a group of scientists with specific views on how the Earth should look; it must be done by a society as a whole. This is where ecology sometimes clashes with laymen, animal right groups and others. (This was why the [newcomer] Grey Squirrel was not eradicated in Lombardia.)

“When we talk about our landscape, it concerns all people who live in it. This is clear on Mount Sutro, but I can give you examples from Europe as well. Ecology should not tell people what they should think, they can decide that for themselves. What ecology should do is give us sound science and let society decide.”

CHARLIE: INVASIVES, NOT EXOTICS

Charlie responded to Gov’s comments:

“I guess I don’t understand your point here. Are you saying you support globalization of ecosystems? I don’t understand why anyone would support converting every ecosystem with similar conditions across the world, into the same thing. That’s what happens if you mix up all the plants… the opportunistic ones take over, because their predators aren’t there also, and you lose a lot of diversity.

“I understand there is a division between invasive and exotic. I try to be very clear: I am not talking about ‘exotic’ plants but about invasive plants. Only 1 in 1,000 introduced plants (or whatever) are invasive… this is true. How does this justify not doing anything about the [0.1%] that cause a problem?

“I reject the equation of ecosystems of plants with human culture; all humans are the same species, and biologically we are even all the same race. We diverged less than 100,000 years ago and since we have long lifetimes, we haven’t diverged enough to form separate species. Also, human societies do not act like plants. It is unfair to compare invasive plant ecology with xenophobia or racism.

“If you ask 100 people if they like a tree, of course 60 will say they like it. If they understood that having this one species of tree means a loss of 40 other species [of plants], maybe they wouldn’t feel the same way.

“Yes, conservation has conservative characteristics and it is a bit odd that in the US it is perceived as a liberal cause. This has more to do with struggles over wilderness designation and regulation of access in the American West than anything. When I objected to being called a conservative, I should have been more specific. I do not support or want anything to do with the Republican Party in the United States.

“Again, climatologists DO have emotional and personal responses to their findings. I don’t see the difference between them and ecologists. Both are dealing with complex systems that are difficult to define, but both have come to very overwhelming conclusions. The connection between INVASIVE species and biodiversity loss is really, really strongly established. I can’t find the list (many pages) of references on CAL-IPC that show this connection. I don’t know why you keep prodding the discussion towards ‘hatred of non-natives’ which is a straw man discussion you are creating… I am talking about INVASIVE organisms, most of which are introduced by humans.”

[Webmaster: The CAL-IPC is not exactly unbiased in this matter; the fear of invasives is exactly why they exist. But perhaps you could link to one or two species relevant to Sutro Forest, like blackberry or black acacia?]

“This is a personal issue for me because I have watched too many ecosystems in California be basically ‘crashed’ (like a computer freezing, or an economic collapse of sorts) from diverse, self sustaining ecosystems, to monocultures of 1 or 2 plants. I realize that in 10,000 years the ecosystems will organize into a much more complex form again, but me and anyone I know will be long, long dead before then.”

[Webmaster: I think you underestimate nature, myself. Within a year, insects, birds and animals will find new niches within that habitat, and start to change it. Other plants will enter and compete. I don’t think it’s going to take 10,000 years to get there. There’s change on a human scale, and change on a scale that’s too small, too fast, too large, too slow. But creating stasis in an inherently dynamic system takes work.]

“Essentially the ecosystems I love are being destroyed, and when I try to protect them I am compared to racists and xenophobes and the Tea Party. Why not recognize they [native plant advocates] are trying to protect places they love?”

[Webmaster: Not the Tea Party!]

GOV: MANKIND IS A DISPERSAL FACTOR

Here’s Gov’s response.

Gov: Okey Charlie, thanks again. I do understand that you feel a loss of what you love in nature and I wish, for you, things were different. Of course our discussion does not have to be solely scientific, although I feel that many of the things being said come from the current ecological mainstream, as can be seen in many organizations turning nativist. I’ll try to separate them.

Charlie: I guess I don’t understand your point here. Are you saying you support globalization of ecosystems? I don’t understand why anyone would support converting every ecosystem with similar conditions across the world, into the same thing.

Gov:

“I have no problem with it. Mankind to me is just a relative new dispersal factor, like the wind, landbridges etc. Regionally, biodiversity sharply rises, with the loss of almost no species. We are talking about thousands of new species at the expense of nearly zero….

“So the homogenization of biota. That is [a subjective] aesthetic. Are New York, Bangkok and Paris boring or the same because of cultural homogenization? Because opportunists like McDonalds, Starbucks but also pizzerias can be found everywhere? I have never heard anyone who visits these cities complain. They remain unique, though they have changed and share more similarities than before.

“For the local populations, are they losing something with the addition of Starbucks and Mac? Could be. But most people must like them, or they would not be there. I bring up this example because ecologists use it up regularly as to show how “bad” this is. They call it the ‘McDonaldisation’ of nature, and it’s presented as something we should dislike. To whom are they talking? Not to the majority of people, I am sure.

“In nature, no plants or animals can establish themselves in every climate, unlike McDonalds. So this won’t happen, but some can be seen in more places. But like cities, these places will still remain unique. Marine ecosystems are much more alike because dispersal is easier. Are these systems less interesting?

“Do you see the difference between the Russian and the Canadian Taiga? Or Tundra? The spruce trees are different but look much alike. Many animals are shared already; like the brown bear, the wolverine, the beaver, the wolf, the fox, or the seal. Only a connoisseur would see the difference. Is any one complaining? Siberia is still very different from Canada, despite the similarities. Either way: this is not a scientific argument. It is a subjective preference.

“Who is going to notice the similarities? The lucky few. Others would have to travel 10,000 km instead of 100 to see a Sitka spruce forest….So for local people, [preserving native ecosystems means that] they lose biodiversity instead of winning anything.

Charlie: I understand there is a division between invasive and exotic. I try to be very clear: I am not talking about ‘exotic’ plants but about invasive plants. Only 1 in 1000 introduced plants (or whatever) are invasive… this is true. How does this justify not doing anything about the [0.1%] that cause a problem?

Gov: “Because ‘invasion’ does not equal ‘problem.’ It equals ‘change.’ To you they are a problem, to me they are not, in general.

Charlie: Also, human societies do not act like plants. It is unfair to compare invasive plant ecology with xenophobia or racism.

Gov: I have tried to explain that the way we think about these newcomers is similar. It is not based on science, it is based on our prejudice and fears . You fail to see the comparison, so maybe I am not clear also. Let me cite Dov Sax in a discussion with ecologists (and he himself does peer-reviewed research on invasions and extinction). I could not say it better myself:

————————————

[Gov quotes Dov Sax]

“So the impacts of exotic species on native biodiversity and ecosystem processes vary widely in kind and magnitude. Whether these are considered to be positive or negative, good or bad is a subjective value judgment rather than an objective scientific finding.

“Scientists are no more uniquely qualified to make such ethical decisions than lay people. Scientists are uniquely qualified to collect the facts and interpret their consequences. It is entirely proper for private citizens, including scientists, to be advocates for positions that promote some combination of self-interest and societal welfare. These positions may be based in part on scientific information, such as the documented extent and likely consequences of global warming or a biological invasion. In their professional roles, however, scientists have the obligation to collect, analyse and communicate such information accurately and objectively. When scientists go further and try to impose their own ethical and moral imperatives on society as a whole, they embark on a slippery slope. They risk compromising the principles of unbiased, objective inquiry that are the essence of the scientific method – and the primary reason why society should support and pay attention to scientists.

“Don’t get us wrong. As private citizens we authors are enthusiastic supporters of actions and policies to reduce the ongoing loss of global biodiversity and homogenization of the earth’s biota. We also stand by our comment, however, that many scientists, managers, policy makers and lay people have a deep-seated prejudice against exotic species that comes close to xenophobia. This is apparent in the adjectives used to describe non-native species and their impacts – invasive, alien, plague, foreign, aggressive, catastrophic, insidious, destructive, decimating, devastating, damaging, threatening, assaulting and flooding – to mention just a few. But worse than such words are the unsubstantiated, unscientific tales, too often promulgated by scientists themselves, that biological invasions are somehow unnatural and that as a general rule invading species dominate ecosystems and cause economic losses, wholesale ecological changes and extinctions of native species. Sometimes they do, but the impacts vary enormously with the species of invader

and the environmental setting.

“Moreover, whether these impacts are perceived as positive or negative, good or bad, varies with the moral beliefs of societies and individuals. When scientists claim that their professional credentials uniquely qualify them to make such moral judgements, they exceed their special, time-honoured roles as unbiased collectors, interpreters and communicators of scientific information.”

————————————

Charlie: If you ask 100 people if they like a tree, of course 60 will say they like it. If they understood that having this one species of tree means a loss of 40 other species [of plants], maybe they wouldn’t feel the same way.

Gov: Read again: they were told why [the trees] were cut down. This was rejected by 65%. Only 15% agreed. BTW exactly the same percentage of people support nativist politicians BTW…

Charlie: I do not support or want anything to do with the Republican Party in the United States.”

Gov: Well, I can understand that!

Charlie: Again, climatologists DO have emotional and personal responses to their findings. I don’t see the difference between them and ecologists. Both are dealing with complex systems that are difficult to define, but both have come to very overwhelming conclusions. The connection between INVASIVE species and biodiversity loss is really, really strongly established. I can’t find the list (many pages) of references on CAL-IPC that show this connection.

Gov: Climatologists do so in private and not in papers nor in books for scholars. It ain’t so and I know so. I have done research myself on this matter…I know climatologists and I know those who had to testify for our government. They have not said the development is bad or good. It’s a scientific fact that the Earth warms. What politicans should think about it was up to them. Climatologists in general behave like Dov Sax thinks ecologists should behave, and I agree.