This continues Paul Gobster’s article from Pt 1.

——————

Landscape and Land Use History

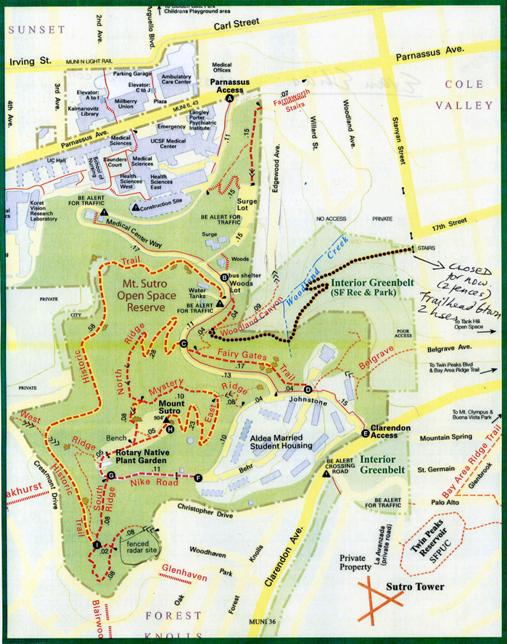

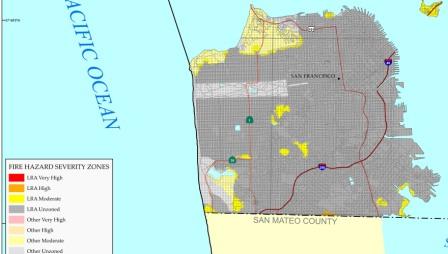

Cranz and Boland (2004a, 2004b) do not identify how the recently developed ecological parks in their sample came into being, but in my own research I found sites originated in two ways: (1) designation of existing park space for ecological management; and (2) purchase or transfer of private or public land for use as new park space. The first type includes parks or portions of parks that may have retained natural characteristics by design or in some cases through neglect and are seen in a new light as having potential for ecological management. Many of the 50 nature areas in the Chicago Park District fall into this category, and range from historic designed landscapes in the naturalistic style such as Montrose Point and the Lily Pool in Lincoln Park; to man-made lagoons such as Lincoln Park’s North Pond and Gompers Park’s lagoon and wetland; to small prairie gardens such as those in Indian Boundary and Winnemac Parks (Figure 1). Many of the 30 natural areas within the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department’s Natural Areas Program were designated within existing parks because of the natural features that still remain; these include lakes such as Pine Lake and Lake Merced and remnant plant communities such as Bayview Hill and Glen Canyon (Figure 2).

Parks of the second type may also have been purchased or transferred specifically because they contain natural remnants or characteristics worthy of protection and restoration in a more public setting. Others may be brownfields or have otherwise been significantly altered by previous uses, and ecological management is used as a strategy for rehabilitation as well as for environmental values as a long-term goal (e.g., DeSousa 2004). Examples of both of these types can be found at the Presidio of San Francisco, a former U.S. Army property in the northwestern corner of the city that in 1994 was transferred to the National Park Service as part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Sites with natural remnants include Lobos Creek and Baker Beach, while Crissy Field includes a major tidal marsh restoration on land that was filled beginning in the 1870s and used for the 1915 World’s Fair and then as an army airfield (Boland 2004) (Figure 2).

As these examples show, urban parks often have a complex landscape history, and restorations that ignore or deny the multiple layers of cultural design and change that may have taken place can lead to a form of museumification that some have called Disneyfication.

Here the complex and sometimes unpleasant storylines are edited from the landscape, leading to a portrayal that is one-dimensional and reinforces positive themes (Huxtable 1997). In many North American projects, restorationists attempt to turn landscapes back to the way they might have been prior to European settlement, even though a site may have since been farmed, filled in, or put to use for a variety of other purposes. Early proposals for ecological restoration of dune communities at the Presidio called for removal of the non-native forests planted by the U.S. Army during the 1880s, some of which were subsequently spared because of their functional and historic values (Baye 2001; Joseph McBride, personal communication, 25 February 2004). Not only can failure to acknowledge these cultural changes reduce the richness of landscape history, but ignoring the extensive landscape modifications of soils, microclimate, and other factors that may have occurred to a site can also limit the success of restorationists in bringing back earlier plant communities.

In addition to landscape history, the museumification of urban parks through restoration can also change the land use patterns of sites. Urban land, particularly parkland, rarely lies unused, and in the advent of restoration this frequently means that some current uses must now be restricted. Like many urban parks in the United States, parks in Chicago and San Francisco went through a period of neglect beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, and not only did less developed spaces become wilder looking, but there was less enforcement of what kinds of activities took place there. In Chicago’s Lincoln Park, the remoteness of Montrose Point made it a popular place for gangs and drug activity, while the rocky gardens at the Lily Pool made an attractive climbing area for children.

In San Francisco, open meadows and wooded paths such as those at Pine Lake became popular areas for walking dogs off-leash, and in some parks where crime and gangs had gained a stronghold, dog owners helped to reclaim the parks for themselves and other users. While restoration has gone far to bring deserved attention and resources back into urban parks and reduce socially undesirable uses, like the naturalistic park movement it has also pruned the spectrum of otherwise acceptable behaviors down to those passive appreciative activities that are deemed appropriate for this revised context to ensure minimal degradation of the now fragile environment.

Characteristics of Restoration Design

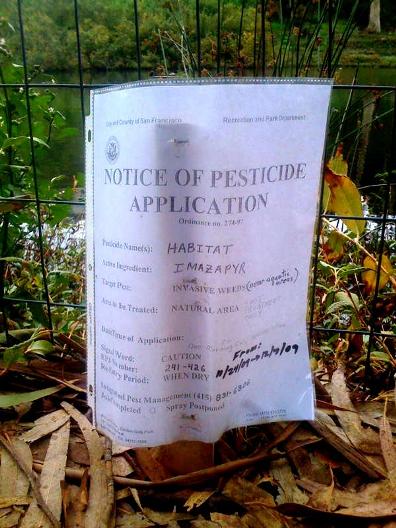

Natural area restorations are sometimes criticized as looking too unkempt when placed in an urban context, and elements of design are often suggested to provide the public with visual cues to signal that these sites are in fact being cared for (e.g., Nassauer 1995). But these design conventions can be taken too far, making restorations into outdoor museum exhibits. At some of the restoration sites in the Presidio, boardwalks direct movement through a site, giving the visitor few choices to see what lies beyond the edge. In some places fencing provides a physical or symbolic barrier between the visitor and the vegetation, adding a further element of separation and distance.

At some locations, plants in the immediate foreground are labeled, and while this helps visitors know what they’re seeing, it also objectifies them and gives the impression that the site is more a botanical collection than an ecosystem. Are the labeled plants representative of those that might appear on an average site or are they plants of particular interest, put there because of their rarity, beauty, or some other characteristic? Do they occur on site in an arrangement or distribution that might occur naturally, or are they planted there like a botanical collection so that visitors might see a range of them in the course of their walk through the site? The ambiguity in presenting nature this way is another aspect of how design can lead to museumification.

Beyond these design elements, how the restoration process itself is implemented in urban parks can also lead to museumification. Here there is a clear contrast between community-based restoration projects and those done by hired professionals, the latter of which are often treated like museum gallery installations. For a complex project like the North Pond restoration, the site is largely fenced off to public use and a team of park professionals and private subcontractors comes in to deal with the various aspects of developing the restoration. Working like any construction project, their sequence of activities includes demolishing existing nonnative species and other discordant elements; bringing the infrastructure of water quality, soil, drainage, pathways, and other human and environmental systems up to acceptable levels; planting and establishing the plant and animal collections; installing fencing, benches, and other site furnishings for visitor control and comfort; and developing signage, brochures, and other interpretive materials.

Hopefully working on schedule and within budget, the restoration is declared “completed” and opened to the public under great fanfare. Restoration done in this fashion may fit within the constraints of an agency’s capital projects procedures but tends to cast nature simply as an artifact under control by humans for humans (e.g., Katz 1992).

Impact on Nature Experience

People experience nature on a variety of levels, from looking out the window to cultivating plants for food and pleasure. Each type of nature experience can yield a variety of benefits to people and it would be wrong to call one better than another. Yet at the same time, urban park restoration has the potential to deliver a broader set of experiences beyond the passive appreciation of nature. In this respect, while some of the urban park restoration sites I looked at in Chicago and San Francisco are visually beautiful and contribute not only to the local environment but also educate people about ecological health and diversity, I feel they are experientially narrow. By truncating landscape history and restricting how the sites are used, and by treating nature as a museum object that is created and presented as a finished product, they limit the range of experiences that urban nature can provide.

Some restoration critics I interviewed in San Francisco spoke about how restoration efforts were reducing the types of nature experiences they once had. One person grew up in a neighborhood above what is now the Lobos Creek restoration and recalled how her everyday explorations in the meadow and forest areas led to her love of nature and desire to pursue a career in biological science. She may have not become so hooked if her interactions with the site were repetitions of the same boardwalk scenery. Another person enjoyed photographing plants and wildlife at Pine Lake near her home and was fearful that the new restoration plan for the site would fence off access to the edge of the lake where all the action was. Several others used their dogs as motivators to take regular walks through natural areas but are seeing that as sites are improved through restoration, access with dogs is being restricted.

My own observations of restoration projects in Lincoln Park conducted before and after their completion corroborate these sentiments, not only in terms of how they restrict people’s type of nature experiences but also raising questions of equity in who gets to have a nature experience. Use of the Lily Pool is now highly regulated and supervised by site docents, and the rock climbing by children that I observed during a site reconnaissance 10 years ago is strictly forbidden. The shoreline of North Pond that had been mowed to the waterline and trampled down to dirt banks by fishermen and waterfowl is now covered in lush vegetation fenced off to access by both user groups. Access to the water’s edge is provided at a few rocky ledges built along the shore but the pond has not been restocked with sport fish as fishing was deemed to be incompatible with the new goals for the restored site.

Even if the pond is eventually restocked, the current design is unlikely to facilitate fishing, for as a manager of a youth urban fishing program told me, similar shore access done for the lagoon restoration at Gompers Park doesn’t work for fisherman because “the access areas aren’t where the fish are” (Bob Long, personal communication, 18 August 2006). Finally, while the restoration of Montrose Point has eliminated gang use, the increased habitat of trees and shrubs has now made it a popular place for cruising and on-site sex. This has created an uncomfortable situation for restorationists and the birding community, and to deter what is perceived as an inappropriate use of park space much of the habitat has been fenced off and dozens of signs have been erected in the name of protecting the environment for migratory birds (Edwards 2005).

Children are a stakeholder group of particular importance when it comes to nature experience, and much attention has been given in recent years to how children in cities are suffering from a “nature-deficit disorder” (Louv 2005). Nature can provide an ideal setting for creative, unstructured play, both for individual imaginations to run free and as a focus for the negotiation of social roles and responsibilities. Digging holes, building forts, climbing trees, catching insects or fish, collecting rocks and flowers, and other activities that are motivated by natural environments can be highly creative endeavors for children and depend on an active interchange between them and the environment (e.g., Johnson and Hurley 2002; Miller 2005; Sobel 1993). The wild and weedy nature that existed in many of these urban park areas prior to restoration provided these sorts of opportunities, and if they weren’t exactly sanctioned no one seemed to care because little effort was being put into managing them. Now displaced by a more ecologically

diverse yet more fragile nature, these kinds of activities are discouraged just as they are in more manicured park settings. Children are much less likely to attain satisfying nature experiences through passive forms of interaction and thus may be disproportionately affected by such changes (Nabhan and Trimble 1994).

The result of this museumification is that we are creating a significant gap in the spectrum of nature experiences available to urban children precisely at the nearby places where children stand the best chances for getting acquainted with nature. Thus while striving to achieve authenticity in the restoration of ecosystems we may be sacrificing the authenticity of children’s nature experiences.

Expanding the Spectrum of Nature Experiences

To me, one of the great ironies in these examples of urban park restoration is that while the product can be a restrictive and objectified nature for some people, the process of restoration as it is practiced by others through volunteer stewardship provides many opportunities for multidimensional, highly interactive nature experiences. Even restoration sites where the initial phases are treated as a construction project usually rely at least in part on a corps of volunteers for subsequent management. These restorationists tramp across natural areas collecting specimens for study and monitoring bird and butterfly populations; they cut and dig and even light fires to burn off invasives and recycle nutrients to the soil; and in doing so they often have profound nature experiences that cut across all dimensions of aesthetic, recreational, social, educational, and even spiritual values (e.g., Grese et al. 2000; Miles et al. 1999; Schroeder 2000).

Thus, if part of the disjunction between the design of nature and the experience of it lies in the difference between who is a visitor and who is a manager, then part of the solution might be to expand the contingent of managers, in effect letting more people inside the gates of paradise. This kind of outreach is happening in many restoration programs, where business groups, seniors, singles, and children are recruited into programs to work on restoration projects in the broader context of community service, improving physical health, meeting people, and learning about nature (e.g., Earth Wise Singles [www.EarthWiseSingles.com]; Mighty Acorns [www.mightyacorns.org]; also see Pretty 2004). The type of hands on interaction with the environment can be geared to the desires and skills of the individual or group, with the goal of changing those seeking a nature experience from detached observer to active participant. Ecological restoration needn’t even be at the forefront of an activity as long as it is compatible with restoration goals. For example, at the Lobos Creek restoration, the federally endangered San Francisco lessingia, a tiny sunflower, requires periodic disturbance to perpetuate itself. The current design and behavioral norms of the restoration project discourage the very kinds of human use needed, and recognizing this site designers have thought about scheduling fun activities like annual “dune dancing” (Terri Thomas and Michael Boland, personal communication, 5 May 2004).

These kinds of outreach programs can go far to build more interactivity into the experience of restored environments, but as most are directed toward specific activities and done on a schedule overseen by supervisory personnel they do not fit into everyone’s nature experience needs or desires. Serving a broader range of individuals may require looking to alternative models of urban natural areas management, particularly ones that allow for more unstructured and perhaps more environmentally impacting activities (e.g., Gobster 2006, 2007). The effect here is to do away with the gates of paradise altogether. If the objective in managing a natural area is not to protect fragile remnant ecosystems, managers might consider allowing environments that may be weedier and more resilient to disturbance so a greater amount of unstructured nature interaction can take place.

For example, in response to trends in the loss of nature experiences by children, the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County in suburban Chicago has initiated an effort that supports and encourages youth to engage in unstructured nature exploration and play such as climbing trees, building forts, and catching and releasing frogs and other small animals (Strang 2006). The teaching of safe and ethical nature play-skills is also built into more structured environmental learning programs, and when time is given during a program to use them it proves to be the high point of the children’s learning experience. At other sites where the protection of a sensitive species or habitat is a particular concern, a natural area that provides the necessary conditions but does not require complete ecological restoration may allow for a greater variety of human uses. Spatial zoning has been applied to some natural areas in San Francisco, where outer areas allow greater use for people and their dogs but still provide a wild buffer for protection of the interior zone. Temporal zoning is another strategy that is being used in other locations, where some uses are restricted during seasonal periods such as bird nesting or migration but at other times are allowed (Ryan 2000).

In their early-twentieth-century park designs, Jensen and Simonds not only pushed the idea of naturalism toward a greater incorporation of regional biodiversity, they also struggled with how naturalistic urban parks might enable children and adults to have more hands-on contact with nature. Children’s gardens, rustic play pools, and play spaces created in forest openings are a few examples of how these designers sought to make what they saw as the virtues of the countryside more accessible to those who lived in cities (Grese 1992; Robert E. Grese, personal communication, 7 May 2007). This struggle continues with twenty-first-century ecological park design, and while our increased knowledge of ecological primacy, nature-deficit disorder, and environmental equity makes the balancing of nature protection and use issues more complicated, it also makes it more incumbent upon us that we try to achieve that balance.

Urban parks needn’t be conceived as either paradises or parking lots, and many alternatives are possible that can creatively expand the spectrum of nature experiences available to adults and children. Is the museumification of nature inevitable at some restoration sites? In cases where species protection is a top priority, human use is very high, or the educational value of a collection outweighs more experiential considerations, such a restoration with its experiential limitations may be the only alternative. But in other cases natural areas managers might relax their assumptions on how restoration should proceed. As a guiding principle of urban park restoration, authenticity should be conceived as having both ecological and experiential dimensions, and management that considers both of these needs can help strengthen the role of urban parks as a bridge between nature and culture.

Acknowledgments

I thank Robert E. Grese, James R. Miller, Robert L. Ryan, and Herbert W. Schroeder for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

References

Ashworth, Gregory J. 1998. “The Conserved European City as Cultural Symbol: The Meaning of the Text.” Pp. 261–286 in Modern Europe: Place, Culture, Identity, ed. Brian Graham. London: Arnold.

Baye, Peter. 2001. Draft Recovery Plan for Coastal Plants of the Northern San Francisco Peninsula. Portland, OR: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Berdahl, Daphne. 1999. “ ‘(N)Ostalgie’ for the Present: Memory, Longing, and East German Things.” Ethnos 64 (2): 192–211.

Boland, Michael. 2004. “Crissy Field: A New Model for Managing Urban Parklands.” Places 15 (3): 40–43.

Carlson, Allen A. 1977. “On the Possibility of Quantifying Scenic Beauty.” Landscape Planning 4 (2): 131–171.

Chicago Park District and the Lincoln Park Steering Committee. 1995. Lincoln Park Framework Plan: A Plan for Management and Restoration. Chicago: Chicago Park District.

Conway, Hazel. 1996. Public Parks. Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications.

Crandell, Gina. 1993. Nature Pictorialized: “The View” in Landscape History. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Cranz, Galen. 1982. The Politics of Park Design: A History of Urban Parks in America.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cranz, Galen, and Michael Boland. 2004a. “Defining the Sustainable Park: A Fifth Model for Urban Parks.” Landscape Journal 23 (2): 102–120.

Cranz, Galen, and Michael Boland. 2004b. “The Ecological Park as an Emerging Type.” Places 15 (3): 44–47.

DeSousa, Christopher A. 2004. “The Greening of Brownfields in American Cities.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 47 (4): 579–600.

Duane, Timothy P. 1999. Shaping the Sierra: Nature, Culture, and Conflict in the Changing West. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Edwards, Jeff. 2005. “Sex in the Age of Environmental Disaster: Sex Imperils Migratory Birds.”

AREA Chicago. http://www.areachicago.org/issue1/migratorybirds.htm (accessed 25 April 2007).

Egan, Dave. 1997. “Old Man of the Prairie: An Interview with Ray Schulenberg.” Restoration and Management Notes 15 (1): 38–44.

Gobster, Paul H. 1999. “An Ecological Aesthetic for Forest Landscape Management.” Landscape Journal 18 (1): 54–64.

. 2001. “Visions of Nature: Conflict and Compatibility in Urban Park Restoration.” Landscape and Urban Planning 56 (2/3): 35–51.

. 2002. “Nature in Four Keys: Biographies of People and Place in Urban Park Restoration.” Paper presented at the conference on Real-World Experiments: Strategies for Reliable and Socially Robust Environmental Research, 3–5 October, Bielefeld University, Germany.

. 2004. “Stakeholder Conflicts over Urban Natural Areas Restoration: Issues and Values in Chicago and San Francisco.” Paper presented at 4th Social Aspects and Recreation Research Symposium, 4–6 February, San Francisco, CA.

. 2006. “Urban Nature: Human and Environmental Values.” Paper presented at the Commonwealth Club of California, 7 April, San Francisco, CA.

. 2007. “Models for Urban Forest Restoration: Human and Environmental Values.” Pp. 10–13 in Proceedings of the IUFRO Conference on Forest Landscape Restoration, ed. John Stanturf. Seoul: Korea Forest Research Institute.

URBAN PARK RESTORATION

. 2008, Forthcoming. “Yellowstone Hotspot: Reflections on Scenic Beauty, Ecology, and Aesthetic Experience.” Landscape Journal 27 (2).

Grese, Robert E. 1992. Jens Jensen: Maker of Parks and Gardens. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Grese, Robert E., Rachel Kaplan, Robert L. Ryan, and Jane Buxton. 2000. “Psychological Benefits of Volunteering in Stewardship Programs.” Pp. 265–280 in Restoring Nature: Perspectives from the Social Sciences and Humanities, ed. Paul H. Gobster and R. Bruce Hull. Covelo, CA: Island Press.

Hall, Marcus. 2004. Earth Repair: A Transatlantic History of Environmental Restoration. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Huxtable, Ada Louise. 1997. The Unreal America: Architecture and Illusion. New York: The New Press.

Johnson, Julie M., and Jan Hurley. 2002. “A Future Ecology of Urban Parks: Reconnecting Nature and Community in the Landscape of Children.” Landscape Journal 21 (1): 110–115.

Jordan, William R., III. 2003. The Sunflower Forest: Ecological Restoration and the New Communion with Nature. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Katz, Eric. 1992. “The Big Lie: Human Restoration of Nature.” Research in Philosophy and Technology 12: 231–241.

Louv, Richard. 2005. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

Miles, Irene, William C. Sullivan, and Frances E. Kuo. 1999. “Psychological Benefits of Volunteering for Restoration Projects.” Ecological Restoration 18 (4): 218–227.

Miller, James R. 2005. “Biodiversity Conservation and the Extinction of Experience.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 20: 430–434.

Nabhan, Gary Paul, and Stephan Trimble. 1994. The Geography of Childhood:WhyChildren Need Wild Places. Boston: Beacon Press.

Nassauer, Joan I. 1995. “Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames.” Landscape Journal 14 (2): 161– 170.

Olmsted, Frederick Law, Jr., and Theodora Kimball, eds. [1922] 1970. Frederick Law

Olmsted, Sr.: Landscape Architect 1822–1903. New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc.

Pretty, Jules. 2004. “How Nature Contributes to Mental and Physical Health.” Spirituality Health International 5 (2): 68–78.

Rybczynski, Witold. 2000. A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the 19th Century. New York: Touchstone.

Ryan, Robert L. 2000. “A People-Centered Approach to Designing and Managing Restoration

Projects: Insights from Understanding Attachment to Urban Natural Areas.” Pp. 209– 228 in Restoring Nature: Perspectives from the Social Sciences and Humanities, ed.

Paul H. Gobster and R. Bruce Hull. Covelo, CA: Island Press.

San Francisco Recreation and Park Department. 2006. Significant Natural Resources Area Management Plan, Final Draft. San Francisco: San Francisco Recreation and Park Department.

Schroeder, Herbert W. 2000. “The Restoration Experience: Volunteers’ Motives, Values, and Concepts of Nature.” Pp. 247–264 in Restoring Nature: Perspectives from the Social Sciences and Humanities, ed. Paul H. Gobster and R. Bruce Hull. Covelo, CA: Island Press.

Simonds, Ossian C. [1920] 2000. Landscape-Gardening. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Sobel, David. 1993. Children’s Special Places: Exploring the Role of Forts, Dens, and Bush Houses in Middle Childhood. Tucson, AZ: Zephyr Press.

Society for Ecological Restoration. 2004. The SER International Primer on Ecological Restoration.

Tucson, AZ.: Society for Ecological Restoration International.

Strang, Carl. 2006. “Places to Play.” DuPage Conservationist Summer: 1.

Wall, Geoffrey, and Philip Xie. 2005. “Authenticating Ethnic Tourism: Li Dancers’ Perspectives.” Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 10 (1): 1–21.

Young, Terrence. 2004. Building San Francisco’s Parks, 1850–1930. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

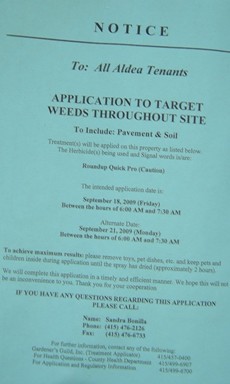

Weeds, dry vegetation, and de-vegetation: bare rock.

Weeds, dry vegetation, and de-vegetation: bare rock.