I (as in I, the webmaster) recently got a legal letter by email from a major law firm representing the San Francisco Parks Trust “and its partner, Sutro Stewards.” (I can’t publish the letter here as the law firm denied permission.)

ALLEGATIONS

It said this website implied the Sutro Stewards were felling trees and applying Roundup. “In fact,” the letter noted, “Sutro Stewards is precluded by the Management Plan from using chainsaws and power brush-clearing equipment.” [ETA2: No chainsaw use, as far as we know. But a power hedge trimmer appears to have been used for “brush-clearing.” ETA2a: The link no longer works; it went to a Sutro Stewards blog post that has apparently been taken down. It was an account by Craig Dawson of how he used a power hedge trimmer to destroy blackberry brush.] Later it says, “volunteer groups such as the Sutro Stewards may not apply herbicides for safety reasons.”

It quoted from UCSF’s 2001 Management Plan, page 69, which talks about volunteers:

The yellow sections were quoted in the legal letter.

The yellow sections were quoted in the legal letter.

CLARIFICATIONS

So I’d like to clarify: We do not believe (and I do not believe we stated) that the Stewards actually felled trees [themselves]. In the referenced post, we were attempting to contrast the “one tree” that Craig Dawson said was removed during trail-work in the UCSF portion of the forest with the large number felled in the City-owned portion. We hope that the re-wording clarifies that point.

Nor do we believe they are actually applying herbicides. The UCSF portion of the forest is, as far as we know, currently herbicide-free. In the referenced post, that is what we were indicating. (We have added a note of explanation on the post.) Herbicides used in the City-owned portion would be applied by Rec & Parks personnel or their contractors.

However, members of the Sutro Stewards have (as is their right), advocated for the use of herbicides and for tree removal as part of the Plan for the forest in community meetings. We assume the herbicides, if used, would be applied by people licensed to do so.

“CONTROL” OF THE FOREST

The third point was that we implied that the Stewards controlled the forest. “One of your most recent posts falsely states that the Reserve is controlled by Sutro Stewards,” it said, and added a quote from our website:

Those who own and control it — UCSF and the Mount Sutro Stewards — do not perceive it as a unique environmental treasure, an urban Cloud Forest with tourist and visitor potential…

But it’s a matter of perception: As the forests of East Africa are locally valued mainly as a source of wood, bush-meat and farmland, it may be that the Mount Sutro Stewards value this glorious forest mainly as acreage where they can implement a native plant introduction.

Here’s an excerpt from their letter, posted only for purposes of discussion:

So again, some clarification is in order.

So again, some clarification is in order.

We do not believe that the Sutro Stewards own the Reserve. In fact, the forest is owned by UCSF (61 acres) and the City (19 acres), and it is these two entities that make the decisions. We would like to clarify that we do not think that the Stewards have any legal control of either the UCSF-owned or the City-owned part of the forest, and that any “control” they have is delegated by the owners.

In our opinion, the Stewards appear to have a close relationship exceeding that of other community groups with these organizations. This appears to empower the Stewards to influence decisions much more than other individuals or groups, and they do not seem to be “just like other members of the community.” Here are some of the observations that influenced our opinion:

- In a meeting in May 2009 called by UCSF to discuss its plans for obtaining FEMA funds to fell trees on the mountain, Craig Dawson made a presentation along with UCSF representatives.

- Subsequently, members of our group asked UCSF for an opportunity to make a presentation at one of their community meetings, and were denied.

- Both UCSF and Rec & Parks have used and published intellectual properties that the Sutro Stewards claim they own, without attribution or protection of copyright — which appears to have the knowledge and consent of Craig Dawson, Executive Director of Sutro Stewards. (See the next section, Copyright, for further discussion.)

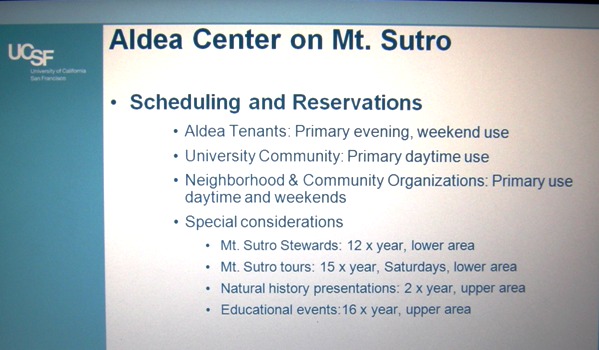

- The Sutro Stewards conducted joint public meetings with UCSF and with the Recreation and Parks Department regarding a trail on Mount Sutro (July, 2009).

- Craig Dawson is leading member of a small Parnassus Community Action Group of UCSF, and in that role co-facilitated a UCSF-sponsored meeting (together with another member, Kevin Hart) about the Open Space Reserve. We did not get the impression that “just other members of the community” like ourselves would be given the same opportunity to present to the group at any UCSF- sponsored event.

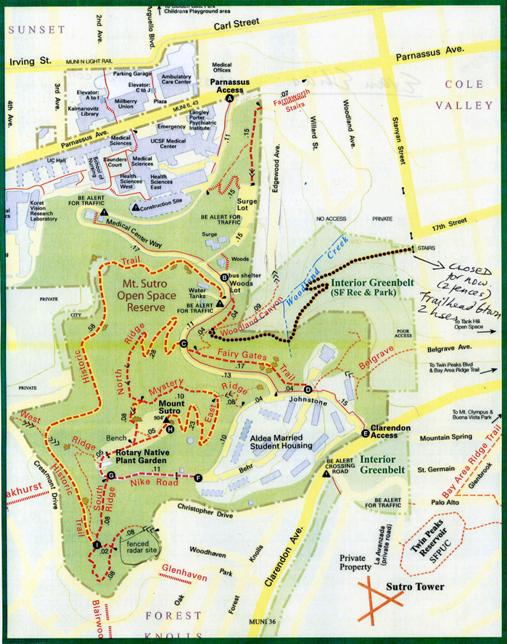

- The trail map published by Pease Press links the logos of the Sutro Stewards and UCSF, as does the trail map published by the UC Regents. This gives the impression of a relationship closer than “just like other members of the community.”

- UCSF’s website recognizes the volunteer contribution of the Sutro Stewards and specifically mentions Craig Dawson. We think it laudable that UCSF should recognize the Stewards’ work in maintaining trails, and note their awards on its website. However, that also gives us an impression of a closer relationship than other members of the community enjoy.

This, together with the quite broad range of physical activities they are empowered to perform — which in themselves can impact the ecology of the forest — makes them in our opinion an important influence on the fate of Sutro Forest. It is this regard we’ve alluded to “control.”

The legal letter says that, “contrary to your published information, UCSF PCAT meetings are sponsored only by UCSF, not Sutro Stewards…” and told us to correct it. We did not anywhere state that the Sutro Stewards sponsored the meeting in our post, Report on UCSF Parnassus Meeting (Nov 2010). Nevertheless, we have inserted the clarification from the legal letter. In the earlier announcement post, the headline was in fact reporting a notification that we received. I have formatted it to clarify that what we published was quoting a notice from a neighborhood organization.

COPYRIGHTS

We respect copyrights. We will not knowingly violate copyrights. As a matter of policy and practice, we seek permission to use materials from others, unless we believe they are in the public domain or under Creative Commons, or in fair use for education or critique. The legal letter claimed we had violated copyrights with some maps.

1) The first alleged that we had “cropped a Sutro Stewards map so as to remove a 2008 copyright notice (Map copyright July 2008, Ben Pease/ Pease Press) and Sutro Stewards trademark” and used it in various places on this and other websites.

We didn’t.

This map was distributed at a public community meeting of the Rec & Parks Department in its discussion of the trail to be opened from Stanyan, with no attribution to the Sutro Stewards, or copyright information. It was actually circulated in this cropped form as “Exhibit B” to a memo by a Rec & Parks Department employee, dated 23rd February 2010. Though other maps — Exhibits A and C in that attachment — incorporated copyright data and source data, this map did not carry either a source or a copyright notice. Presumably Craig Dawson, Executive Director of the Sutro Stewards was aware of this; he is listed in the same memo as ‘People to Contact’.

As such, I considered it (and believe it to be) non-copyright, and used modified versions of that map to show the effects of the planned actions on the mountain.

[ETA: The minutes of the Commission hearing show that Ben Pease was also present. The map copyright that the law firm accuses me of violating was in his name. So this becomes even more puzzling. It seems the Stewards claimed copyright in a map that originally belonged to Ben Pease and did not seem to have been assigned to the Stewards. But the map used without attribution and copyright information was made part of the public record at a public hearing, presumably with Ben Pease’s consent as well as with Craig Dawson’s consent. This looks to me like placing it in the public domain. If that’s so, then once it’s been placed in the public domain, it can’t be withdrawn.]

As demanded by the letter, I will take down those maps.

For actual use on trails, we refer you the reader to the Sutro Map at the excellent Pease Press Cartography. (We note that the map we downloaded on 26 Jan 2011 carries no copyright notice. It also carries the logo of the Sutro Stewards and UCSF together at the top.)

2) The second map they objected to was the one showing the Demonstration areas and the planned new trails. This was modified from two separate maps to present both the Demonstration Areas and the trails in one map.

The source of these maps was a UCSF report published in November 2010 (UCSF Open Space Reserve Community Planning Process Summary Report). That report did not attribute the maps to the Stewards nor carry any copyright information. Since the Sutro Stewards [ETA: according to the legal letter] provided these maps to UCSF, we presume they were aware of this. We had and have no way of knowing that the Stewards own these maps.

(In fact, the maps appear to be based on a very similar trail map of the forest, with some text by Sutro Steward Dan Schneider and photography by Sutro Stewards Executive Director Craig Dawson, was published as “Map & Guide to the UCSF Mount Sutro Open Space Reserve.” That was copyright to The Regents of the University of California. There was no separate copyright or attribution for the actual map as distinct from text and photographs.)

As the UCSF report had apparently been prepared as a basis for public information and discussion, and that is the purpose for which we are using it, we consider this fair use. UCSF — which is aware of our website and of me personally as the webmaster — has never objected to our use of their images for the purpose of discussion and critique even though we disagree about the forest.

As demanded by the letter from the law firm representing the San Francisco Parks Trust and the Sutro Stewards, I will take down that map.

OUR PHILOSOPHY IN RUNNING THIS WEBSITE

This website seeks transparency, publishes both information and opinion, and encourages spirited discussion. We’re a grass-roots, community-based effort. We do not solicit or accept monetary donations.

To all our readers, we’d like to take a moment to explain our philosophy for this website.

- We try to avoid inaccuracies. We do our research. When reporting on meetings, we do so from contemporaneous notes taken at the meetings, and try to post soon afterward while our memories are fresh, often the same night. When reporting from the field, as far as possible we include photographs.

- We correct mistakes. We are open to comments from anyone (though all comments are moderated because of spam), and we try to respond. If you find mistakes, you are welcome to contact us in comments or by email. If our data are wrong, we’ll do an ‘Edited to Add’ to correct it.

- We do express our opinions, cogently and we hope convincingly.We avoid ad hominem arguments. We are willing to engage with those expressing other points of view. We believe in opponents, not enemies.

- We keep our comments open to other opinions, even opposing ones. Only once so far have we closed off a discussion for reasons of length and repetition. We have not, so far, banned anyone from commenting here. We use the New Scientist magazine’s house rules as a general guide. (We are not affiliated in any way with that magazine, except as readers.) We explained our policy on editing comments here.

- As we said above, we respect copyrights and will not knowingly violate copyright. We will use material we believe to be non-copyright, public domain, Creative Commons, or fair use unless someone convinces us we’re wrong. If we are indeed mistaken, we will take down the relevant material. [ETA: In this case, we do not believe we are actually mistaken, but we have taken down the maps anyway.]

###

We have to wonder, given that we are open to correction of errors (and have done so in the past at the request of UCSF and others) why did the Sutro Stewards, Craig Dawson, and the San Francisco Parks Trust think it was necessary to send a strongly-worded legal letter?

The target plant is yellow oxalis, which flowers all over Twin Peaks in the spring, providing nectar for bees and butterflies. Unfortunately, it’s considered an invasive non-native plant, so there it goes. We imagine a goodly amount of Garlon 4 Ultra will need to be used over a pretty broad area, since the oxalis is not exactly confined to a few odd patches.

The target plant is yellow oxalis, which flowers all over Twin Peaks in the spring, providing nectar for bees and butterflies. Unfortunately, it’s considered an invasive non-native plant, so there it goes. We imagine a goodly amount of Garlon 4 Ultra will need to be used over a pretty broad area, since the oxalis is not exactly confined to a few odd patches.