One of the saddest myths about eucalyptus is that it causes the death of small birds by “beak-gumming.”

MISLEADING ILLUSTRATION

According to this myth, small birds like kinglets foraging in eucalyptus flowers accumulate gummy residues that suffocate them. It’s all because Californian birds have short beaks compared to the longer beaks of Australian birds that co-evolved with eucalyptus. It is usually illustrated by the picture here (taken from an NPS brochure).

It’s a myth.

A new article (reprinted here with permission) by Lynn Hovland in the Hills Conservation Network newsletter describes where this myth originated, and how eucalyptus-phobes seized on it, passing it into “the conventional wisdom” as one birder phrased it. And it explains why it gets its facts wrong. In summary:

- The theory (and picture) conveniently ignores a host of small-beaked Australian birds that forage in eucalyptus.

- The source of the gum is undetermined; the eucalyptus flower is not especially deep.

- Other birders have not found numerous dead birds under eucalyptus.

Read the whole article below.

————————-

BIRDS AND BLUE GUM: LOVE OR DEATH?

Brochures distributed by various agencies in northern California state that the flowers of eucalyptus trees kill birds. According to these brochures, birds feeding on insects or on the nectar of eucalyptus flowers may have their faces covered with “gum” and die of suffocation. Luckily for the birds, according to one brochure, most of them prefer native vegetation, and avoid eucalyptus groves.

These stories are, of course, extremely upsetting to all of us who love birds.

The bird-suffocation story began with a 1996 article by Rich Stallcup, a legendary birder who writes for the Pt. Reyes Bird Observatory. In the PRBO Observer, he reported that, on one day in late December, he counted, in one eucalyptus tree: 20 Anna’s Hummingbirds, 20 Audubon Warblers, 3 Orange-crowned Warblers, 10 Ruby-crowned Kinglets, a few starlings, 2 kinds of orioles, a Palm Warbler, a Nashville Warbler, a warbling Vireo, and a summer Tanager.

That was an unusually large number of birds, even for Stallcup to see in one tree, but what most surprised him, he says, is what he found under that blue gum eucalyptus tree: a dead Ruby-crowned Kinglet, its face “matted flat from black, tar-like pitch.”

Years before, Stallcup recalled in the article, he had found “a dead hummingbird with black tar covering its bill” under eucalyptus trees. This was all Stallcup needed to come up with his theory about what had happened.

This theory is now stated as fact in restorationist literature and it is stated three times as fact in the Plan/EIR issued by the East Bay Regional Park District in August 2009.

Ruby-crowned Kinglet, San Francisco. Credit: Will Elder, NPS.gov

Stallcup theorizes that North American birds are different from birds indigenous to Australia. He speculates that North American birds such as kinglets, warblers, and hummingbirds have evolved short, straight bills while Australian birds evolved long, curved bills. Thus, he says, when American birds with short bills seek nectar or insects on eucalyptus flowers, they have to insert their whole head into the blossom, so they get gummy black tar all over their faces.

We have great respect for Stallcup’s ability to identify birds. But we have a few problems with his theory.

Australian Weebill. Credit: Stuart Harris

1. A bird-loving friend who has photographed birds in Australia points out that Australian field guides show birds with a wide variety of bill length and curvature. When he was in Australia, he saw birds with small bills just like American kinglets and warblers. “How do you suppose the Australian Weebill got its name?” our friend asked. Many of us not so familiar with Australian birds have seen parakeets and other small small-billed parrots native to Australia. Weebills and many other American and Australian birds with small bills forage on eucalyptus leaves or flowers.

To see more birds of Australia, go to this terrific website. It features photos of many small-billed birds.

Blue gum eucalyptus flowers on tree, March, 2010. Credit: John Hovland,

2. Where’s the gum? The flower of a blue gum eucalyptus tree has no gum, glue, or tarlike substance on it or in it. The gum in “gum trees” refers to the sap or resin that, in some species, comes from the trunk. Other species of gum trees, such as the sweet gum (Liquidambar) are common sidewalk trees in Berkeley and Oakland. The flowers on the blue gum eucalyptus are white or cream-colored with light yellow or light green centers. There is no black, sticky, gummy or tarry substance in or on the living flower. In fact, both the Ruby-crowned Kinglet and the Australian Weebill are leaf-gleaners. They take insects off leaf surfaces, not from flowers. If the kinglet had gum on its face, the gum did not come from a eucalyptus blossom.

3. A euc flower looks most like a chrysanthemum, with longer petals. Unlike a morning glory, the euc flower is not shaped like a tube that a bird would need to poke its bill into to get nectar or insects. A hummingbird is more likely to pick up a sticky substance from inside a cup-shaped tulip, poppy, or any of the tiny tube-flowers such as California fuchsia, Indian paintbrush, watsonia, or honeysuckle that hummingbirds love. Common sense tells us that no bird, even a tiny one, could suffocate while feeding on a euc flower or leaf.

Photo of Watsonia, Willow Walk, Berkeley, 2010. Credit: John Hovland.

4. We have all seen hummingbirds poking their beaks into tube-like flowers. If you peel back these tube-like flowers, you will sometimes find a sticky substance on your finger. You’ve probably seen birds, especially tiny hummingbirds, sipping from these flowers. How do they escape getting nectar on their faces? An article in the NY Times proves truth is stranger than the fiction of suffocated hummingbirds. The article explains that a hummingbird gets nectar from a flower by wrapping its tongue into a cylinder to create a straw about ¾ inch long extending from its bill. This means that a hummingbird’s face does not touch the surface of a flat type of flower such as the flower of a blue gum eucalyptus.

After Stallcup wrote his article in 1997, it was accepted by birders and eucaphobes all across America. In January, 2002, Ted Williams, wrote about the “dark side” of eucalyptus in his opinion column called “Incite” for Audubon Magazine.

Stallcup, he wrote, had told him he had found 300 dead birds over the years “with eucalyptus glue all over their faces.” Williams wrote that the bird artist, Keith Hansen, who illustrates Stallcup’s articles, had found “about 200 victims.”(How did one kinglet and one hummingbird in 1997 add up to 500 victims by 2002 even though few if any other people have seen even a single victim?) Williams and Hansen also describe the suffocating material as “gum.”

Williams, in that same over-the-top column, dares to contradict Stallcup, claiming that he has heard only one Ruby-crowned Kinglet in a eucalyptus grove, and has never actually seen any birds in eucalyptus trees. Yet he repeats (and exaggerates) Stallcup’s story about eucalyptus suffocating birds. The National Park Service, U.C., EBRPD, and the Audubon Society have spread Williams’ interpretation of Stallcup’s story—apparently without questioning any part of it.

Stallcup and Williams are bird-lovers and writers. They are not scientists. David Suddjian, a wildlife biologist, has read Stallcup’s theory about birds suffocating on the “black pitch” of eucalyptus flowers, but in his article, “Birds and Eucalyptus on the Central California Coast: A Love-Hate Relationship,” he casts doubt on Stallcup’s claim that the kinglet (and other birds) could have been suffocated by eucalyptus flowers. Here is an excerpt from his article:

“. . . in my experience and the experience of a number of other long-term field ornithologists, we have seen very little evidence of such mortality. It has been argued that the bird carcasses do not last long on the ground before they are scavenged. However, when observers spend hundreds of hours under these trees over many years but find hardly any evidence of such mortality, then it seems fair to question whether the incidence of mortality is as high as has been suggested. Not all bird carcasses are scavenged rapidly, and large amounts of time under the trees should produce observations of dead birds, if such mortality were a frequent event. . .more evidence is needed.”

The Suddjian article is not generally favorable to eucalyptus trees. However, Suddjian notes that more than 90 species of birds in the Monterey Bay Region use eucalyptus on a regular basis. Additionally some rare migratory birds bring the total to 120 birds seen in euc groves. These include birds that use eucalyptus trees, leaves, seeds, or flowers for breeding, nesting, foraging, and roosting. A complete list of birds that depend on eucalyptus trees is too long to include here. We encourage you to click on the link to the Suddjian article so you can look for the names of the various bird species and note how they use—and depend on—eucalyptus trees.

The following excerpt is from the section “Wildlife” in BugwoodWiki, an article on eucalyptus globulus (blue gum) by the Nature Conservancy. It is from a field report “Eucalyptus Control and Management” (1983), compiled by the Jepson Prairie Preserve Committee for The Nature Conservancy’s California Field Office:

“Over 100 species of birds use the trees either briefly or as a permanent habitat. The heavy-use birds feed on seeds by pecking the mature pods on trees or fallen pods; so they must wait for the pods to disintegrate or be crushed by cars. Among the birds that feed on seeds in the trees are: the Chestnutback Chickadee and the Oregon Junco.

“Examples of birds that feed on ground seeds are the Song Sparrow, the Fox Sparrow, the Brown Towhee, and the Mourning Dove.

“Birds that take advantage of the nectar from blossoms either by drinking the nectar or by feeding on the insects that are attracted to the nectar include Allen’s hummingbird, Bullock’s Oriole, Redwinged Blackbird, and Blackheaded Grosbeak.

“Birds that use the trees as nest sites include the Brown Creeper, which makes its nest under peeling shags of bark and feeds on trunk insects and spiders, the Robin, the Chickadee, the Downy Woodpecker, and the Red Shafted Flicker. The Downy Woodpecker and the Red Shafted Flicker peck into the trunk of dead or dying trees to form their nests. When these nests are abandoned, chickadees, Bewick Wrens, house wrens and starlings move in. Downy Woodpeckers use dead stubs to hammer out a rhythmic pattern to declare their territories.

“The Red-tailed Hawk prefers tall trees for a nesting site. It therefore favors eucalypts over trees such as oak or bay. Great Horned Owls use nests that have been abandoned by Red-tail Hawks or they nest on platforms formed between branches from fallen bark. The Brown Towhee and the Golden-crowned Sparrow are birds that use piles of debris on the ground for shelter during rains.”

Notice that this article, written for the Nature Conservancy after weeks of observing birds in eucalyptus groves, does not mention finding any suffocated birds under the trees.

When we asked Chris Davey, president of Australia’s Canberra Ornithological Group, if there could be any truth to the story that eucs suffocate birds, he replied, “It’s a wonderful thing these urban legends!”

So how did those dead birds end up under eucalyptus trees?

A friend suggests (only half-seriously) that a few birds (including the two that Stallcup says he found) got some kind of sticky goop on their faces from another source. He theorizes that when the birds realized they were dying, they returned to the eucalyptus trees, and, chose to die under them because they had loved the eucalyptus trees so much.

—Lynn Hovland

——————————–

A few further thoughts to this article:

- No analysis of the material that apparently suffocated the birds has been published. Apparently, it was just assumed to be eucalyptus resin.

- No necropsy results indicating that the birds indeed died of suffocation was published either. The “gum” on the face could have been incidental to death from other causes.

- What about the benefits the tree provides? It helps a large number of birds to survive by providing cover and a winter food source (insects and nectar). It’s been suggested that if the eucalypts were felled, the birds would migrate south. In fact, the habitat to the south is not exactly unspoiled. Cutting down eucs would reduce net habitat, and thus, bird populations.

Finally: Here are two more short-beaked birds from Australia.

Jacky Winter, Australian bird. Photo credit "Aviceda" (Creative Commons)

Australia's Rose robin, photo credit "Aviceda" (Creative Commons)

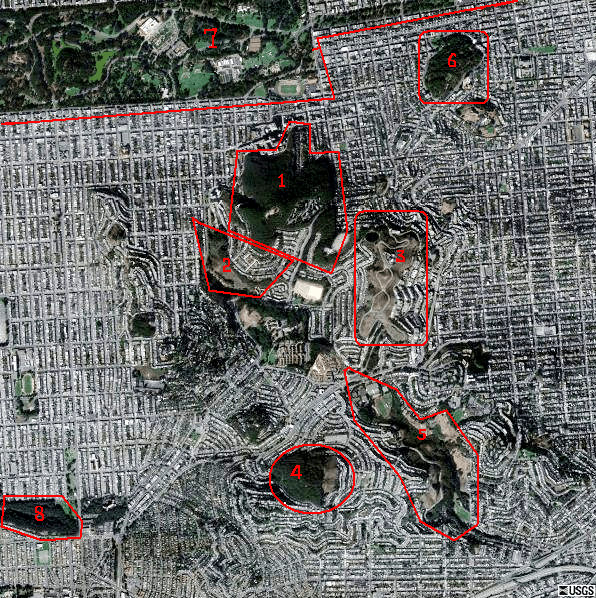

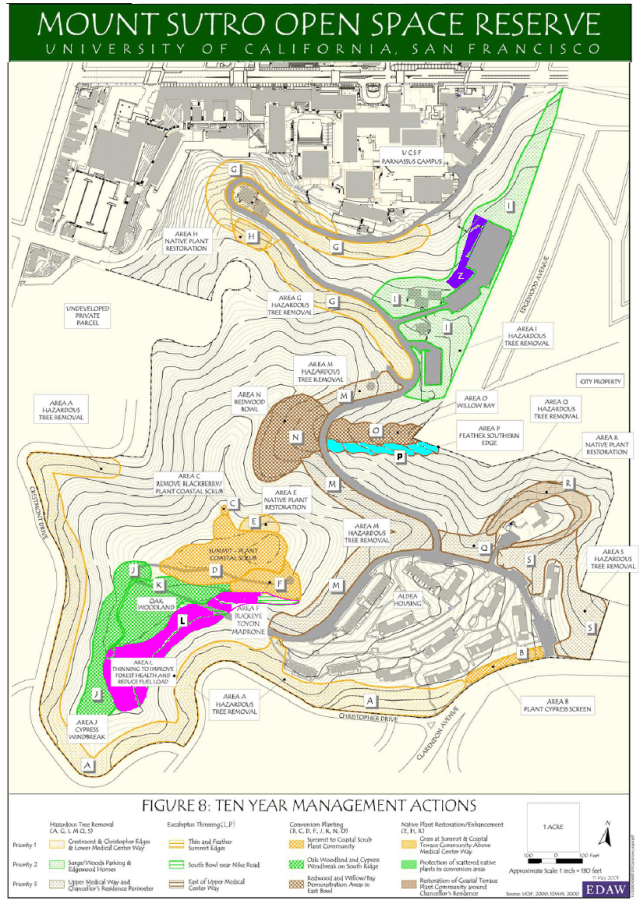

This is area of the forest once formed a dense screen between the Aldea campus and the Forest Knolls area. In fact, the Aldea student housing was not visible from Christopher or Clarendon. (See map on left.)

This is area of the forest once formed a dense screen between the Aldea campus and the Forest Knolls area. In fact, the Aldea student housing was not visible from Christopher or Clarendon. (See map on left.)

Hills Conservation Network

Hills Conservation Network